There is a considerable correlation between trauma and substance use disorders, as described in my policy brief (“The Brief”). The Brief addressed the impact of substance use education on adolescents with mental illness and this blog post is dedicated to transforming that knowledge into practice. Before describing methods of how to transform the knowledge known about trauma and substance use disorders, I believe that it is imperative to first describe the multitude of factors that come into play surrounding this issue. First, let’s discuss what the issue is.

The Issue

According to studies mentioned in my Policy Brief, the results of these studies “show that PTSD precedes substance use disorders (Jacobsen et al., 2001).” These studies “found that 25 of the 33 participants (75%), who disclosed substance use reported a history of trauma (Deas, 2006).” Children who have experienced Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) “have been found to have a higher prevalence in the population with substance use disorders compared to the general population. According to Fernández-Montalvo, ‘a positive association has been found between ACEs and the development and severity of SUD in adolescence and adulthood.’ (Fernández-Montalvo et al., 2021).”

Let’s discuss where and how a person might be discovered with a substance use disorder. There are a variety of ways in which a person with a substance use disorder comes into contact with health care centres. An article titled “Trauma-informed Approaches in Addictions Treatment” focusing on the impact of substance use disorders among women describes the core approaches using multilevel, multiple intensity supports. They first describe the five tiers of support:

- Tier 1 – Community-based and outreach services

- Tier 2 – Brief support and referral by a wide range of professionals

- Tier 3 – Acute, proactive outreach and harm reduction services

- Tier 4 – Structured and specialized outpatient services

- Tier 5 – Intensive residential treatment

These people can show up in emergency centres due to overdoses, socio-economic situations such as “housing instability, homelessness, criminal behaviours (victim or perpetrator) and incarceration, the transmission of HIV due to IV drug use or high-risk sexual behaviours, and unemployment or dependence on welfare.” (Daley, 2013).

Being a person with a substance use disorder already places you into a vulnerable population, however, these people could have overlapping minority identities, such as:

- people who are in abusive families

- people who have a racial or ethnic minority

- children

- elderly

- chronically ill or disabled people

- homeless people

- incarcerated people

- immigrant people

- people from the LGBTQ+ community

- refugee people

- mentally ill people

You might be wondering why there is a considerable correlation between trauma and substance use disorders. In order to answer this question, it is important to understand what trauma is. According to the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, trauma is defined as:

“an experience that overwhelms an individual’s capacity to cope. Whether it is experienced early in life—for example, as a result of child abuse, neglect, witnessing violence and disrupted attachment—or later in life due to violence, accidents, natural disasters, war, sudden unexpected loss and other life events that are out of one’s control, trauma can be devastating. Experiences like these can interfere with a person’s sense of safety, self and self-efficacy, as well as the ability to regulate emotions and navigate relationships. Traumatized people commonly feel terror, shame, helplessness and powerlessness. The terms violence, trauma, abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are often used interchangeably. Trauma expert Stephanie Covington suggests that one way to clarify these terms is to think of trauma as a response to violence or some other overwhelmingly negative experience. Trauma is both an event and a particular response to an event; PTSD is one type of disorder that results from trauma. There are multiple types of trauma. The definitions used in psychiatric manuals have been built upon the groundbreaking work of Judith Herman, who contributed to our understanding of the levels of complexity of trauma and to our understanding of safety and connection as a necessary first stage of healing from trauma. Definitions of trauma useful to support awareness for clients of substance use services and for service providers have been published by the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health.”

According to the article The Many Types of Vulnerable People Impacted by PTSD, which discusses the prevalence of trauma in different populations, author Javanbakht found that “nearly 8% of the U.S. population fulfills diagnostic criteria for PTSD at some point in their lives. In special populations with high levels of trauma exposure, such as combat-exposed veterans and first responders, PTSD may be as prevalent as 30%. Trauma exposure runs up to 90% among urban people living in poverty, and about 20% of this population may meet the criteria for PTSD. PTSD is very prevalent, ranging between 20% and 80%, among refugees and civilian victims of torture.”

It is hard to imagine living as a person who experienced one traumatic event that was completely out of control, and using substances to cope with that traumatic experience, but to imagine that this person is any one of the vulnerable populations listed above? What if this person is a homeless youth or a person from the LGBTQ community? The risk of trauma skyrockets, so this begs the question of what can we do to support these individuals.

What Can We Do?

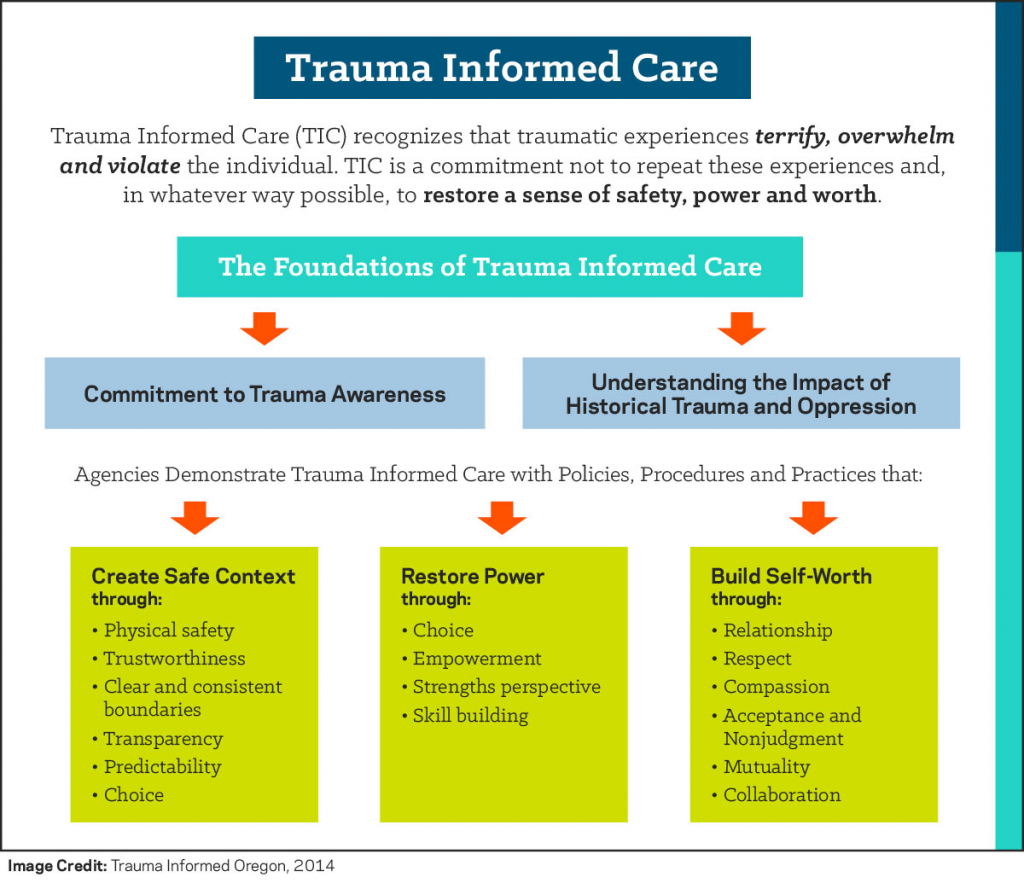

Trauma-informed care is an approach that reframes the narrative of shame and blame “what is wrong with this person?” to an understanding, empathic narrative of “what happened to this person?” It shapes the understanding of “problem behaviours” to coping mechanisms that the person used to adapt to traumatic experiences. This approach takes the onus off of the victim and empowers them by providing a safe understanding space. Trauma-informed care does not require disclosures of trauma, or treatment of trauma. This approach aligns to where the individual feels the most comfortable and progressively works with the individual to improve how they feel.

Trauma-informed care can be further explained within the table below:

According to the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, trauma-informed approaches are defined as:

“Trauma-informed services take into account an understanding of trauma in all aspects of service delivery and place priority on trauma survivors’ safety, choice and control. They create a treatment culture of nonviolence, learning and collaboration. Working in a trauma-informed way does not necessarily require disclosure of trauma. Rather, services are provided in ways that recognize needs for physical and emotional safety, as well as choice and control in decisions affecting one’s treatment.

In trauma-informed services, there is attention in policies, practices and staff relational approaches to safety and empowerment for the service user. Safety is created in every interaction and confrontational approaches are avoided. Trauma-specific services more directly address the need for healing from traumatic life experiences and facilitate trauma recovery through counselling and other clinical interventions.

Advocates for trauma-informed approaches in the substance use treatment field do not ask substance use treatment professionals to treat trauma, but rather to approach their work with the understanding of how common trauma is among those served, and how it is manifested in people’s lives. It could be said that trauma-informed approaches are similar to harm-reduction-oriented approaches in that they focus on safety and engagement. In trauma-informed contexts, building trust and confidence pave the way for people to consider taking further steps toward healing and recovery while not experiencing further traumatization.”

So, how can trauma-informed care be put into practice? According to the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, the key principles of trauma-informed approaches are as follows:

“Researchers and clinicians have identified key principles of trauma-informed practice, which have parallels with principles underlying evidence-based practices in the mental health and substance use field.

- Trauma awareness: All services taking a trauma-informed approach begin with building awareness among staff and clients of: how common trauma is; how its impact can be central to one’s development; the wide range of adaptations people make to cope and survive; and the relationship of trauma with substance use, physical health and mental health concerns. This knowledge is the foundation of an organizational culture of trauma-informed care.

- Emphasis on safety and trustworthiness: Physical and emotional safety for clients is key to trauma-informed practice because trauma survivors often feel unsafe, are likely to have experienced boundary violations and abuse of power, and may be in unsafe relationships. Safety and trustworthiness are established through activities such as: welcoming intake procedures; exploring and adapting the physical space; providing clear information about the programming; ensuring informed consent; creating crisis plans; demonstrating predictable expectations; and scheduling appointments consistently. The needs of service providers are also considered within a trauma-informed service approach. Education and support related to vicarious trauma experienced by service providers themselves is a key component.

- Opportunity for choice, collaboration and connection: Trauma-informed services create safe environments that foster a client’s sense of efficacy, self-determination, dignity and personal control. Service providers try to communicate openly, equalize power imbalances in relationships, allow the expression of feelings without fear of judgment, provide choices as to treatment preferences, and work collaboratively. In addition, having the opportunity to establish safe connections— with treatment providers, peers and the wider community—is reparative for those with early/ongoing experiences of trauma. This experience of choice, collaboration and connection is often extended to client involvement in evaluating the treatment services, and forming consumer representation councils that provide advice on service design, consumer rights and grievances.

- Strengths-based and skill building: Clients in trauma-informed services are assisted to identify their strengths and to further develop their resiliency and coping skills. Emphasis is placed on teaching and modelling skills for recognizing triggers, calming, centering and staying present. In her Sanctuary Model of trauma-informed organizational change, Sandra Bloom described this as having an organizational culture characterized by ‘emotional intelligence’ and ‘social learning.’ Again, parallel attention to staff competencies and learning these skills and values characterizes trauma-informed services.”

Take Home Note

Trauma-informed care needs to become the standard of care when addressing people with substance use disorders. The next time you see a homeless person on the side of the road with a glass bottle in a paper bag and a flimsy cardboard sign, instead of asking yourself “what is wrong with this person? Why is it others’ responsibility to help them” try asking yourself “what happened to this person to put them in a vulnerable position to require support from complete strangers?” Changing the dialect and approaching situations differently with these vulnerable individuals will create an environment of healing, inclusiveness and community support and drive change and improved social and emotional well-being.

References

Kidd, M. (2022). Adolescent Substance Use and Mental Illness: Comorbidity and Access to Services [Policy Brief]. Carleton University. https://cuportfolio.carleton.ca/view/view.php?t=8f7657ab1462dbed5c94

Jacobsen, L., Southwest S., Kosten T. (2001). Substance Use Disorders in Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Review of the Literature. American Journal of Psychiatry. 158:8, 1184-1190 https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184

Deas, D. (2006) Adolescent Substance Abuse and Psychiatric Comorbidities. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67: 18-23. https://www.psychiatrist.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/10501_adolescent-substance-abuse-psychiatric-comorbidities-epidemiology-survey-assessment-comorbidity-outc.pdf

Leire Leza, Sandra Siria, José J. López-Goñi, Fernández-Montalvo. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and substance use disorder (SUD): A scoping review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Volume 221, 108563, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108563.

Gendering the National Framework. (2010). Trauma-informed Approaches in Addictions Treatment. British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. https://cewh.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2010_GenderingNatFrameworkTraumaInformed.pdf

Daley, D. (2013). Family and social aspects of substance use disorders and treatment. Journal of Food Drug Analysis; 21(4): S73–S76. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2013.09.038

George, O. (2022). Pet Therapy in Addiction Treatment [Image]. Addiction Resource. https://addictionresource.com/guides/pet-therapy/

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2014). The Essentials Of Trauma-Informed Care Series. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Trauma-informed-Care-Toolkit-2014-en.pdf

Javanbakht, A. (2022). The Many Types of Vulnerable People Impacted by PTSD. Giving Compass. https://givingcompass.org/article/the-many-types-of-vulnerable-people-impacted-by-ptsd

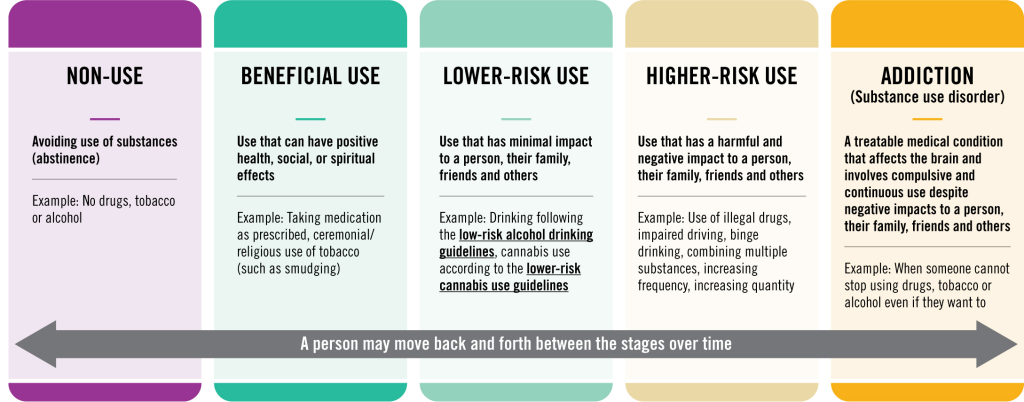

About Substance Use [Image]. (2022). Health Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/about-problematic-substance-use.html

Tkach, M. (2018). Trauma Informed Care for Substance Abuse Counseling [Image]. Hazelden Betty Ford. https://www.hazeldenbettyford.org/education/bcr/addiction-research/trauma-informed-care-ru-118

Why We Use the Term Substance Use Disorder Instead of Substance Abuse [Image]. (2022). Turning Point of Tampa. https://www.tpoftampa.com/why-we-use-the-term-substance-use-disorder-instead-of-substance-abuse/

Recent Quote the Raven Posts

Read the latest from our student Bloggers

Ask Me

Ask Me